Not too long ago scientists believed that babies were born with their brains completely wired but new research has since revealed that the brain carries on growing at a very rapid pace, especially during the first three years of life.

Newborns arrive with about 100 billion neurons or brain cells, which form connections called synapses or neural pathways that allow information to travel around the brain.

Synapse formation is most intense from ages 0-3, after which brain development consists mainly of eliminating unused synapses. At eight months, an infant could have 1,000 trillion synapses but by the time he is ten this number may have been pruned down to 500 trillion. In the brain’s ‘use it or lose it’ selection system, connections that are not frequently activated are discarded.

Therefore, the richer a child’s environment and experiences, the greater will be the number of connections in his brain and the better his ability to learn.

Babies who play often and who are frequently held and touched develop larger brains with more neural pathways than do their counterparts who receive less attention and care. A child’s cognitive abilities grow in direct relation to the quality of childcare received.

A baby’s early experiences and interactions with the environment are, therefore, critical in shaping the way his brain develops. What he contacts and perceives in those early years will, literally, shape who he will become in his later years.

This finding has far-reaching implications for parents and caregivers everywhere because of the critical, one-off period during which they can ensure the child’s optimum development and growth.

It has sparked many debates and discussions about what policymakers, caregivers, educators and parents can do in order to take advantage of this window of opportunity to help children build better brains.

Many early childhood programs have seized on these findings, claiming that it is never too early to start teaching a child and providing them with ‘brain food’. Early learning concepts such as the Glenn Doman Method and the Shichida Method claim to cultivate the genius in every child by taking advantage of the young child’s rapid brain growth.

However, academics may not be the developmentally appropriate way to provide stimulation for the young child.

More than a hundred years ago, Rudolf Steiner, Austrian philosopher and founder of the Waldorf school, stressed that early academics do not strengthen the young child’s development, but instead undermines it.

This has been echoed by Jane Healy, a leading authority on brain development and learning, who warned that early pressure on preschoolers was a prescription for trouble, resulting in problems in motivation and achievement that could create learning disabilities.

In contrast, what the young child needs for his intellectual maturation is nurturing relationships; in particular, he needs the security of an unconditional bond with a primary caregiver, preferably his mother, from which he can confidently reach out to explore his world.

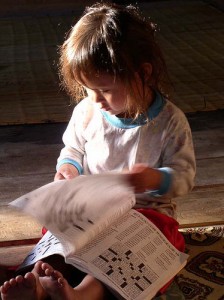

Much of the exploration at this stage is done through play, which engages the two main ways that a young child interacts with his world: sensing, through seeing, hearing, smelling and touching; and doing.

World-renowned thinker, author and advocate of evolutionary child-rearing practices Joseph Chilton Pearce, calls this the mother matrix.

In his groundbreaking book Magical Child, Pearce explains that human intelligence unfolds according to a precisely coordinated, genetic plan, with every step forward dependent on a solid foundation of bonding and safety for the child.

As an infant develops, Pearce believes, he shifts from matrix to matrix, starting with the womb as his first matrix, to his mother (0 to 7 yrs), to the earth (7-11 yrs), to the self (11-adolescence), to the mind or the mental world of thought (sometime after maturity).

The child moves from a concrete, physical intelligence to an abstract one. At every shift he needs to be securely grounded in the earlier matrix in order to fully explore and move into the next.

If this feeling of a safe space is not there, then instead of being free to explore and develop intellectually, the child will spend much of his energies defending himself against unseen enemies and trying to secure for himself that which he feels is lacking.

Research done at the Institute of HeartMath in Boulder Creek, California, show that the way we feel affects our intelligence and our awareness.

“When we are in a positive feeling state our higher cognitive abilities are facilitated – often resulting in enhanced focus, memory recall, comprehension and creativity”, HeartMath researcher Rollin McCraty said in his paper ‘The Scientific Role of the Heart in Learning and Performance’.

This has enormous implications on how children learn and how their brains develop.

“Children’s emotional experience, how they feel about themselves and the world around them, has a tremendous impact on their growth and development. It’s the foundation on which all learning, memory, health and well-being are based,” says Pearce.

“When that emotional structure is not stable and positive for a child, no other developmental process within them will function fully. Further development will only be compensatory to the deficiencies.”

Educational thinker and author John Holt put it very succinctly in his book How Children Learn: “We think badly, and even perceive badly, or not at all, when we are anxious and afraid.”

Once about five years ago, I experienced this first-hand when taking piano lessons from the teacher who also taught my daughter.

As an adult student, I was pretty conscientious about practising and completing my theory homework. One day in class while I was valiantly trying to play a piece that had been introduced the week before, I sensed the teacher’s impatience with me.

Even though she tried hard to suppress it, I knew that she was getting increasingly annoyed with my clumsiness. In response, my brain automatically tripped and began sending mixed-up signals to my fingers, which started stumbling even more.

I felt fear stab my heart and cold sweat started to trickle down my face. I was no longer able to make sense of anything the teacher was saying but it suddenly became startlingly clear to me why my daughter had lost interest in playing the piano.

“When we make children afraid we stop their learning dead in its tracks,” Holt says. “It is love, not tricks and techniques of thought, that lies at the heart of all true learning.”

How very true!